By Tom Roush

The basic facts about the Big Bend area and national park are easy enough to acquire; it is over 800,000 acres of preserved land yet one of the least visited of the 61 national preserves of the United States. It takes its name from the massive left turn that the Rio Grande makes as it snakes its way to the Gulf of Mexico. That big bend in the river is what gives a mapped outline of Texas its iconic shape. The park is a part of the massive Chihuahuan Desert complex that makes up much of Northern Mexico and West Texas, which is characterized by high mountains, little rainfall, and an incredible mix of flora and fauna. Statistical descriptions of the area could go on forever.

But no one seeks out a visit to a statistical place on the map; people go for what that location does for them and it is said that all the world’s geographies serve some human purpose. The mountains, for example, are for the mind; wise men retreat to them. The oceans and rivers are for the body; young and old bathe in the healing waters. The desert is for the spirit; seekers risk their lives in the dry environment to see visions and journey inward.

Not captured in the statistics about Big Bend is that it is blessed with all three environments; mountain, river, and desert. There are mountains difficult to ascend but reward the seeker with a spectacular view from the top. There are calming rivers that carve deep canyons and also form boundaries between two nations linked through a shared geography and a complex native and European history. And, there are dry deserts that bloom with fragile beauty where one can walk in a quiet so profound that one’s own breath can be heard.

As a place on the map of human desires, Big Bend has a statistical coefficient of one. It stands alone. There are many wonderful places on the map, and only one Big Bend.

I came to Big Bend with my middle son, John, shortly after we moved to Texas. Big Bend ranks high on all the lists of favorite hiking spots for avid outdoor people, and I was sold on the descriptions of its 150 miles of trails. John’s childhood was coming to an end, and in the long run up to his high school graduation, we had hiked all over Florida, and even traveled to Southern California and hiked its many canyons and coastlines. A trip to Big Bend was to mark the end of an era and challenge us both. We hiked the mountain trails together and walked all 12 miles of the South Rim Loop trail and then climbed Emory Peak. Our trips to Big Bend made memories for a lifetime.

After graduation, John worked for a few months in a restaurant, and then he joined the Marines. He is his own man now. Those miles we marked off together on the South Rim trail really did mark our final steps together where I was the leader. From Emory Peak onwards, we saw two futures; his and mine, and they were to be different. Being successful as a parent means letting them go.

But, fortunately for me, John has a little brother, Jordan, and as the youngest has gotten older, he has gotten taller and stronger. John had moved at a familial pace all his life and so for the trips to Big Bend, I made them exclusively him and me. We traveled, camped, and hiked at a grown up pace and John excelled in flexing his adult like strength and stamina. But with John off to the Marines and Jordan bigger and stronger, now it was Jordan’s turn, and we both wanted to go to the same place: Big Bend.

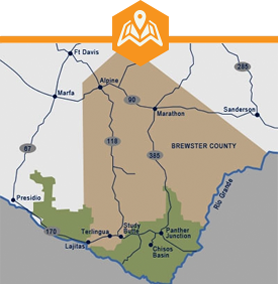

We live in Houston Texas, and even though we are still in the same state with Big Bend, its 650 miles to the funky town of Terlingua, where we usually stay (Terlingua is right outside the entry to the park). Distance is the top reason stated for why Big Bend is so sparely visited, but that seems odd to me. It’s no further to Big Bend from Albuquerque, NM than from Houston, or from Dallas, or from Phoenix, AZ. It’s only a little further from Houston to Terlingua than from Denver to Terlingua. Big Bend is not far from several growth metros.

So, while distance may be a factor, I suspect something else is at play. Something about mindset maybe. Big Bend is at the end of the earth if you view your universe as being the good ol’ US of A. And it is; the entire park is named for the shape of the river the forms the boundary for the jumping off place to the wild and lightly governed parts of Mexico. Yellowstone National Park has far more visitors each year than Big Bend, but it’s a long way from any metropolis. Yellowstone, however, has better iconography, perhaps, and the mystical ‘Old Faithful’ geyser. More movies were shot in Montana and the surrounding area; “Yellowstone” is a current show starring Kevin Costner. The place clearly has great PR.

Distance may be a factor to visiting Big Bend, but oh, what a glorious distance it is. If one is driving, it’s likely that I-10 will be a part of the trip and the exit point will be at Fort Stockton. From there, you head south and the landscape turns in to an incredible mix of watercolor mountains in the distance and long flat spaces that time has forgotten. Across the landscape, one could imagine epic battles between competing dinosaurs, or a scene from any Star Wars movie. Southwest Texas is a giant movie set; a T-Rex or an Imperial Walker would fit in nicely here. Each hill reveals a new and impossible vista for mile after mile until finally, the hills are upon you and you enter the area called Study Butte, pronounced ‘stoody’ which rhymes with duty, and ‘bewt’ which rhymes with newt.

This is the area where Terlingua scatters across the landscape. It is often called the “Terlingua Ghost Town” because the area is dotted with the roofless husks of the old miner residences. The area was the location for cinnabar mining at the turn of the 20th century and when the industrial materials derived from cinnabar were replaced by other industrial processes, the town was abandoned and not really occupied again until the hippy days of the sixties. There are a couple of gas stations there now, a few restaurants, and lots of places to stay, but the town is for the most part ‘out of time’ meaning it has no strong since of current space. It is not an old colonial town or remnant of the Spanish Empire or a sacred native gathering place. The new buildings are right beside the old rock rectangles of stacked local stone where the miners once lived.

Jordan and I arrived and checked in at the Chisos Mining Company motel, which is named as a sort of homage to the history of the town and area. The Chisos Mountains are part of the vast ‘Trans-Pecos’ range which dominate West Texas. There is no motel at the Chisos Mining Co motel, as motels are normally understood, but we picked up the keys to our cabin which was down a canyon a few hundred yards away. Our cabin was clean and comfortable and it had a full kitchen which was good. There are not many restaurant options in Terlingua, and there is no fast food that I noticed, and so cooking either in a small kitchen or at a camp site is a real benefit. It was quiet at our cabin, and from the front porch we listened as a group of chickens down the canyon crowed and in response, another group of chickens up canyon would respond. Our cabin was positioned between permanent residents of Terlingua, which is mostly rural. The sound of the chickens was soothing, and in due course, we ate and went to sleep early.

In the three days that followed, Jordan and I hiked all the zones of Big Bend, from mountain to river. We began on the Lost Mine Trail which is challenging, but easier and shorter than Emory Peak. At the top, we were treated to a spectacular view, with vistas that went on for at least 100 miles deep in to Mexico. We were looking at the back of Emory Peak and at the South Rim trail across the massive canyon. It could not have been better or more rewarding for a trail of only 4 miles. We became so familiar with the shape of Emory Peak that we began to use it as a landmark wherever we were in the park.

The other landmark we used was we drove through the park was the unmistakable cleft in the rocks where the Rio Grande comes out of the cliffs at Santa Elena Canyon. Because the Lost Mine Trail is fairly short, we finished by noon and set off for Santa Elena Canyon, visible in the distance. The entire park has roads that lead from one trailhead to the next and just driving these two lane black tops is a visual feast.

We arrived and headed for the trail head at Santa Elena Canyon. People splashed in the shallow water where the Rio Grande river exits the sheer canyon walls. We headed up a flight of steps and walked along the path that follows the US side of the canyon in for about a half mile. For our efforts, we were rewarded with the echoes of walking in a deep canyon and stepped through and around the dense river cane that grows along the banks of the Rio Grande. The sound of the gentle river mixes with the wind in the river cane to make a peaceful rustling. We walked in shadow since the canyon walls block out direct sunlight for all but a few minutes each day. Just looking at the tiny river and the deep gorge it has created teaches in a way no words possibly could the power of geological time. Water carves, and rock gives way.

Evenings in Terlingua start with the slow sunsets which color the sky in beautiful clichés that would seem trite anywhere else. Photographers call the final period of the day ‘magic hour’ when the sun is filtered through the atmosphere as it lowers, and in Big Bend, all the magic hour properties are exacerbated. When the show ends, the stars take over and one can see the glow of the Milky Way in the sky. Most people never experience true dark because of the lighting in cities, but at Terlingua, we could experience a real nighttime sky, and see the stars the way that most humans saw them for millennia.

Jordan and I headed to a local restaurant called The Starlight Café, to get something to eat. The building was a movie theater back in the mining days, and it was abandoned, and the roof burned but the place has since been restored and turned in to a popular eatery with an outdoor bar which is where we went. We both had some warm chili and allowed the comforting glow of people talking wash over us which was familiar after the day on the sparsely populated trails.

The next morning, we were up before sunrise and in the park as the sky played out the sunset in reverse. Various shades of blue and orange and pink lit up the sky as we reached the trail head at Mule Ears. The trail is named for two massive rock formations that jut up from the ground in the distance. The two ears get larger and larger as you walk the trail, but it happens slowly. This trail is considered desert and there is virtually no gain in elevation and no shade, but the desert in Big Bend is the lushest I have ever seen. There are several types of cactus and flowers and brush that mix in together like the most lovingly planned landscape. Everything is a painting with the giant and distant Mule Ears as a deep counterpoint. Jordan and I walked mostly in silence, noting the many incredible and massive cactus plants that grew more detailed as the sun got higher. I noticed that the sound of my feet walking on the dust was muted and I could hear Jordan breathing, and then I could hear the blood rushing through my ears. It was QUIET. Wonderfully so. The Lost Mine trail had rushing wind in the background, and Santa Elana Canyon had the gurgle of water and the rustle of river cane. Mule Ears has nothing. My beating heart was the soundtrack unless Jordan spoke.

Like going to a huge museum, eventually beauty fatigue sets in and we began to chat. We stopped and looked closer at the many plants that surrounded us and marveled at the detailed structures and shapes their leaves and branches made. When the Mule Ears loomed over us and we met another trail that went deeper in, we turned back. Mule Ears had affected us both.

The afternoons are the peak of the desert heat. In the fall, winter, and spring the heat is tolerable, but we generally stayed off the trails passed noon. By five o’clock, however, the sun is headed down again, and the temps drop in preparation for the next magic hour light show.

Late in the afternoon, we went to the Equestrian Center and the Lajitas Golf Resort and Spa. It is on the western edge of Terlingua, and since there is only one road that goes east and west, it is easy to find. Because something is easy to find does not mean I can find it, so I had to stop in the lobby of the resort to ask where to find the Equestrian Center. The lobby has all the signs of luxury accommodation; plenty of helpful employees, high ceilings, photos of the past, halls that mark how to get to the pool, golf pro shop, and restaurants. I was directed to the Equestrian Center where Jordan and I had booked a sunset horseback ride. I have rented horses before and the experience was generally marked as negative because the horses were ornery and dangerous and the guides were young and unconcerned with safety. The experience at Lajitas is not that; the horses were well behaved and calm, and the guides were at front and back, and the path to the peak where we stopped for wine and cheese was well marked and clear. We rode in peace and strung the horses to a long beam and then walked to a picnic table where the food was waiting. From here, we watched the sun decline in the west and then rode the horses back in the twilight. It was a perfect short evening of horseback riding, and now Jordan talks of little else except how he wants a horse.

Our final day at Big Bend started with a long breakfast and showers. Both of us were tired from all the walking and on the third day, we had floating on the agenda. We dressed warmly and headed to the Far Flung Outdoor Center where we picked up the vans that took us far west on Highway 170. This highway hugs the route along the Rio Grande and passes through the Big Bend State Ranch State park, which is its own special place outside the national park boundaries. After several miles of more jaw dropping scenery, we reached the place where small boats and kayaks put into the river. These landings are mostly just breaks in the tall river cane that have a dirt road available to back the trailers with the boats down to the water.

The rest of the day was spent paddling lazily along the Rio Grande and talking to the guides about the river and its complicated history. The Rio Grande has headwaters in the United States, way up in Colorado. It is supposed to be fed by the runoff from the Rocky Mountains, and when it was allowed to flow as designed, it was a far larger river that carved the canyons we were now floating through. Far up the canyon walls are signs of where the river used to be before so much of it was diverted in Colorado and New Mexico to be used as city water supplies and for agriculture. The Rio Grande, or the Rio Bravo del Norte as the Mexicans call it, is the 20th longest river in the world and was at one time a torrent of water that was open to commercial traffic. Those days are long gone and the river is more of a stream that is no more than 60 feet deep at its deepest point. Only a treaty with Mexico assures that the river will flow at all and there have been many times that the river failed to maintain enough volume to reach the Gulf of Mexico at its terminus point.

But on our day, it was flowing nicely and we paddled through the massive canyons and at one point, stopped on the Mexican side of the river to share a few snacks and take pictures. Jordan was then able to say he had traveled to Mexico which he had, and we exited the river as easily as we had entered.

A final trip to the Starlight Café marked the last evening in Terlingua before we had to pack and head north, towards Alpine, Fort Stockton, and then eventually, home.

After three days, we had hiked the mountains, hiked along and been on the river, and walked through the startling quiet and beauty of the high desert, and rode horses to a mountain top to watch the sun setting. And still, we both felt as if we had only just begun to appreciate what was there in front of us. What would it look like under a blanket of snow? What if the river were higher or lower? What would be possible in the rain or summer, when the sun would drive the desert temps much higher? We didn’t know, but we wanted to know. How much could visitors know of this land anyway? The Terlingua residents surely knew more than they let on, and while they were friendly and helpful, one got the impression as one gets in the world’s sacred spots that the local population tolerates visitors because they have to, and when we leave, they go back to the worship of the land. But Big Bend doesn’t have that many visitors, and so in a sense, when you’re there, you’re local. You have to be. There just aren’t so many people to distract. The land pulls you in, like it or not, and quickly, your mind, body, and soul begin to breathe deeply of a place God touched. Getting there is part of the journey and being there is just the beginning. The place is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, as they say, and no journey fully reveals the place. Perhaps when Jordan is gone, I’ll go back alone and go deeper in to the Big Bend experience. Maybe I’ll walk those trails with a grandchild. Until such time, I walk my normal days at home with the Big Bend experience tucked away in my experiences kit bag, which sustains my mind, body and soul through the days that pass before I return.