By Joe Nick Patoski

The Big Bend is Texas’ playground – the land of wide open spaces, rugged mountains, towering canyons, and sprawling desert with a river running through it.

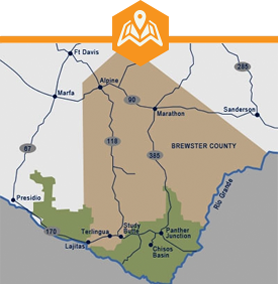

Millions of years of erosion created the big bend in the Rio Grande’s from Colorado to the Gulf of Mexican and gave the region its name. Most of the Big Bend, from Marathon through Big Bend National Park, to the communities of Study Butte, Terlingua, and Lajitas lies within Brewster County, the biggest county in Texas, which happens to encompass more territory than the state of Connecticut, even though the human population numbers less than ten thousand.

In other words, there is plenty of elbow room, with more than a million acres of public lands along with even more accessible private lands waiting to be explored.

Don’t get me wrong. The Big Bend ain’t easy. According to one local legend, if something doesn’t bite, stick, or sting, then it’s a rock. Another pearl of wisdom describes the Big Bend as the land where rainbows wait for rain. Occupying most of the extreme southwest corner of Texas, it’s a long way from everywhere else. The closest commercial airports are more than two hundred miles distant.

Too often, distance, physical expanse, and isolation prove too intimidating for anyone but the most intrepid traveler to take the leap. Don’t let that stop you. If you’re willing to make the effort, the payoff is immersing yourself in the Texas you’ve always imagined, and having it all practically to yourself. For folks like that, including you, here are my Ten Tips how best to experience the Big Bend.

DECOMPRESS IN MARATHON

Start by taking the road less traveled into the Big Bend from Fort Stockton, US Highway 385 south. Once you’ve passed Six Shooter Draw, the land opens up and mountains rise up out of the landscape, while billboards, telephone poles, and other trappings of the modern world peel away.

Once you’ve arrived in the tiny town of Marathon, exhale. Relax. Lighten up. You’re not in the city anymore. Read a book. Strike up a conversation. Locals will talk your ear off if you give them a chance. Rent a bicycle. Do nothing at all.

Marathon is home to the Gage Hotel, the old railroad hotel that has expanded over the years to include an authentic Mexican hacienda addition, Los Portales, that is a personal favorite, Captain Shepard’s Inn bed and breakfast, and, most recently, the Wilson House/Casa Jardin addition across the railroad tracks and adjacent to the 27-acre Gage Gardens, a meticulously landscaped desert garden chock full of native plants, rose garden, fruit orchard, vineyard, ponds, and fountains with a mile-long dog friendly walking trail.

The Gage Gardens isn’t the only significant gardens in Marathon. Two blocks behind the Gage is Eve’s Garden, a whimsically designed, brightly-colored “organic bed and breakfast and ecology resource center,” as it describes itself. Part hippie haven, part small-town Mexican hotel with a covered atrium jam-packed with bougainvillea and other tropical and desert plants, Eve’s is a destination unto itself. Each of the seven custom-built guest suites is unique. The laid-back central courtyard is designed for lingering and for conversation. The Galleries at Eve’s Garden displays works of local and regional artists. The art part of Marathon extends beyond Eve’s Garden to the Evans Gallery showcasing the photography of James H. Evans, who has published several large photography books on the region; and to The Klepper Gallery featuring the work of writer-photographer E. Dan Klepper.

The art part of Marathon extends beyond Eve’s Garden to the Evans Gallery showcasing the photography of James H. Evans, who has published several large photography books on the region; and to The Klepper Gallery featuring the work of writer-photographer E. Dan Klepper.

Take it easy and get some rest. Big Bend National Park beckons, forty-five miles south.

SAY IT RIGHT

For the record, Marathon is pronounced “mare-uh-thun.” Study Butte is “stoo-dee-byoot.” Terlingua has three syllables with no “a” after Ter.” All three are minor nits to pick, but knowing the correct pronunciation is one way to distinguish locals from tourists.

BIG BEND 101

To better understand the story about where you are, download the Visit Big Bend app to your smart phone at justahead.com.

Then hit the road. Ten miles south of Marathon is a small roadside park with an historical marker for Los Caballos.

The “horses” the name refers to are deformed bands of rocks from two converging geological formations emerging out of nearby slopes – mountains 90 million years old intersecting with younger mountains 40-60 million years old, geologically speaking. This is where the Rockies meet the Appalachians.

The speed limit drops to 45 mph once inside the national park. Twenty-two miles past the Persimmon Gap entrance and eight miles south of the Panther Junction visitor center is the recently opened Fossil Discovery Exhibit.

It’s worth the pullover to get an idea of the plants, sea creatures, and dinosaurs that once roamed this space over tens of millions of years ago as it transitioned from ocean bottom to dense forested swamp.

The visitor center at Panther Junction in the national park and the Barton Warnock Center in Lajitas, operated by Texas Parks & Wildlife, both have interpretive exhibits explaining the natural and human histories of the region, as well as desert gardens showing off indigenous plants of the Big Bend.

THE NATIONAL PARK YOUR WAY

Hurry-hurry Ding-dings who think they can experience the 800,000 acres of Big Bend National Park in a single day better think again. Slow down, pardner. Take it easy. You’re not in the city anymore, remember? If you must pass through in a rush, here are three ways to do it. Budget three days and you can do all three, and come away with a real Big Bend experience.

Option 1: Head straight to the Chisos Basin and hit the trail into the high country via the Pinnacles Trail up to the South Rim. It’s a twelve-mile roundtrip that’s physically strenuous and requires plenty of water, good hiking sense, and at least eight hours. The nearby Lost Mine Trail is a shorter 4.8 mile roundtrip climb into the high country that can be completed in a few hours.

Option 2: Head to the Chisos Basin for breakfast, a looksee, and a ranger talk, if one is scheduled. Then descend from the basin and head west on the main park road before turning left onto Ross Maxwell Drive. The thirty-mile road passes the historical Castolon trading post and numerous other points of interest and ends at Santa Elena Canyon. This narrow crevice surrounded by sheer walls rising more than 1,000 feet is the most majestic of the three major canyons in the national park (although the remote Mariscal Canyon and the easier-to-access Boquillas Canyon are nothing to sneeze at). An improved trail just under a mile in length leads into the canyon. From Santa Elena, it’s close to an hour to the west entrance of the national park by the unpaved Maverick Road, or an hour and a half by looping back via Ross Maxwell Drive.

Option 3: Big Bend National Park is the only national park to offer a cultural experience in another country. Head southeast from Panther Junction to stock up on drinks and ice at Rio Grande Village, the campgrounds and RV park where the warmest temperatures in the park are usually recorded. Then drive a mile farther east to the Boquillas crossing. After checking in with park personnel, who make sure you have your passport with you, it’s a short walk to the river where two boatmen wait in an aluminum johnboat to paddle you across. Once on the south bank, a man collects the $5 roundtrip fare and arranges rides into town by horse or motor vehicle for another $5 per person roundtrip.

Boquillas is a timeless Mexican village of 300 or so residents recently electrified with solar panels. The town almost died when the informal border crossing was shut down in 2002, although some local men to work as Diablos, the fire-fighting team trained by national park personnel who fight fires across the American West every summer.

When the crossing reopened in 2013 with a customs house on the US side, Boquillas’ economy rebounded, even though there still isn’t much to do in village by most tourists’ standards. Once you receive your stamped visitor permit in the customs house in town, there are a couple restaurants, a bar, and two gift shops to visit. The old Buzzard’s Roost Bed & Breakfast, the inspiration for Robert Earl Keen’s song “Gringo Honeymoon” is shuttered, but there are rooms to rent at the old reliable cafe, Jose Falcon’s, if you want to stay overnight. The namesake of the establishment founded in 1973 passed away, but his daughter Lilia and her husband have taken over operations, while his widow Ofelia oversees the kitchen. The menu has expanded considerably beyond the old three bean and cheese tacos for a dollar to include regional offerings such as enchiladas montadas, while a sun deck has been added outside.

A hot springs and the remnants of a bathhouse are just off the path between the village and the river.

After being rowed back to the United States, clear customs by placing your passport in a high-tech processing machine and then speaking by telephone with an inspector in El Paso. From the crossing, it’s about five miles to the turnoff to the ruins of J.O. Langford’s Hot Springs Resort, developed in 1909. One man’s vision of a health spa built around therapeutic waters remains a popular destination to soak your bones, no matter what time of day or moonlit night.

Note: the Boquillas, Mexico crossing is open from 9 to 6 Wednesday through Saturday and closed Mondays and Tuesdays.

EXPLORE A HIDDEN GEM IN STUDY BUTTE

Study Butte is the commercial center just outside the western entrance of the national park, as well as the beginning of the Greater Study Butte-Terlingua-Lajitas metropolitan area where a couple thousand residents live. The Cottonwood store, a grocery/hardware/general store across the road, is last chance to load up on supplies before entering the park.

For those exiting the national park, the nearby RV park, Big Bend Resort and Adventures, and the Easter Egg Motel offer the first opportunities to take a shower or bed down for the night. No matter if you’re coming or going, Many Stones in Study Butte is worth a visit for its collection of rare stones, fossils, gems, and all kinds of cactus and other desert plants for sale.

Study Butte is less well-known as the sneak route to Indianhead. The green Indian Head Road sign behind the motor inn part of the Big Bend Resort and Adventures complex points to an unpaved road that winds around desert flats for about five miles to a wide-open parking area a couple hundred yards from a fence marking the western boundary of Big Bend National Park. A break in the fence allows hikers to enter and pick up a faint trail less than a mile long through a jumble of boulders at the base of a rocky slope. Bear left on the trail to find boulders pocked with drill holes and marked with petroglyphs made by ancient Big Bend residents.

Indian Head Road is also a great spot for stargazing away from the lights of Study Butte.

SIT ON THE PORCH IN TERLINGUA

The ghost town of Terlingua is technically the ruins of the old mining town where mercury was extracted until the 1940s. In the 1970s, Terlingua was reborn as a quirky desert refuge for iconoclasts, misfits, cyclists, river runners, biologists, paleontologists, and park personnel. Exotic sculptures, the historical cemetery, adobe ruins, and a teepee across the road from a Pennsylvania Dutch tiny house greet drivers entering the ghost town, signaling you’re Somewhere Else now.

Late every afternoon, the disparate community that lives among the ruins and the scattering of off-the-grid dwellings nearby shows up to sit and visit and mingle alongside tourists on the long porch in front of the Terlingua Trading Company general store. Nothing really much happens on the porch, other than some small talk and folks picking out some music now and then. At sunset, all eyes look east, not west, to watch the sinking sun light up the western wall of the mighty Chisos Mountains, the centerpiece of Big Bend National Park. When the majestic light show concludes, it’s only a few steps to the adobe façade entrance of the Starlight Theater restaurant and saloon, Terlingua’s popular dining spot where locals sing for their supper. If you’re lucky, Butch Hancock might be performing.

If the ghost town is too civilized for your tastes, head east a couple miles and party like the Flintstones at La Kiva, the recently reopened semi-subterranean cave bar-restaurant built into the hillside above Terlingua Creek.

The first Saturday in November, Terlingua transforms into Chili City with not one, but two world championship chili cook-offs held within a few miles of one another. The Chili Appreciation Society International, which sanctions cook-offs around the world, holds their finals on grounds west of the ghost town. The fifty-first edition of the considerably looser and slightly wilder Frank X. Tolbert-Wick Fowler Cookoff honoring the instigators of the chili cook-off concept is held a mile east of the ghost town behind the Terlingua store.

GET ACTIVE IN LAJITAS

Lajitas is best known as a golf resort and spa, but the planned development by the historic river crossing of the same name is also the jumping off point for active rec adventurers. Hiking and cycling trails in Big Bend Ranch State Park are only a few miles west, including the Fresno Sauceda Loop, which has been designated an epic trail by the International Mountain Biking Association. Lajitas also has its own network of cycling trails near the Lajitas airport, and the trailhead to hike up to the Mesa Anguila in the national park begins by the golf course.

Zipline? Lajitas has one. Horses? Or course. The Lajitas Stables and Big Bend Stables in Study Butte offer guided short term and multiday horseback trips.

RUN THE RIVER

The Rio Grande flows through three major canyons – Santa Elena, Mariscal, and Boquillas – inside the national park, with two other large canyons, Colorado and Madera, upstream in Big Bend Ranch State Park. Downstream, the Lower Canyons on the officially designated Wild and Scenic stretch of the Rio Grande is the most isolated river adventure in the southwest, requiring six days minimum to paddle. The payoff are canyons as majestic as those inside the national park, and numerous hot springs on the river and in side canyons. Unlike stretches of the Rio Grande upstream, springs along the Lower Canyons guarantee a good flow for safe passage by canoe year-round. Hire a guide for this one, regardless of your paddling skills.

Big Bend River Tours, Desert Sports, and Far Flung Outdoor Center all schedule guided river trips and rent canoes and small inflatable rafts whenever the Rio Grande is up and running, which isn’t always the case. It pays to call ahead. Far Flung, which began running guided river trips on the Rio Grande in the 1970s, has expanded operations to include paddleboards, Jeep rentals, offroad tours, and ATV rentals with new log cabin casitas on site for rustic luxury lodging.

Desert Sports focuses on cycling tours in addition to river trips. Co-owner Mike Long was instrumental in designing mountain biking trails in Big Bend Ranch State Park.

DRIVE THE RIVER

The fifty-mile El Camino del Rio, the River Road formally known as Texas Farm-to-Market Road 170, is Texas’ most scenic highway. Shadowing the Rio Grande from Lajitas west to Presidio and shadowing the international border between the United States and Mexico, the tight, shoulderless two-lane blacktop cuts through some of the most remote country you’ve ever experienced – rugged mountains, sprawling rubble-strewn draws, and broad floodplains, with all kinds of weird geological phenomena interspersed, such as mounds of buff-colored volcanic tuff and spines of protruding rocks called dikes poking up through volcanic ooze hardened tens of millions of years ago. Except for stray cattle, several trailheads leading to the backcountry of Big Bend Ranch State Park, wild javelina, and the occasional passing motorist, it’s pretty much just the road, you, and a whole lot of big empty. No wonder NASA’s first lunar astronauts trained nearby.

Lajitas is your last chance for gas or services until Presidio.

Maybe you don’t have time to do the whole one hundred-mile roundtrip, which can take all day if you pause along with the way at points of interest such as the ruins of the Contrabando movie set, Closed Canyon, and Fort Ben Leaton, and have lunch in Presidio. At the very least, make the 15-mile drive west from Lajitas up one of the steepest grades of any Texas highway (14%) to the top of the Big Hill. The 400-foot promontory above the river plain promises stunning vistas of Colorado Canyon and the Santana Basin, the Rio Grande, and distant mountain ranges in every direction.

FLY THE BIG BEND

I’ve experienced the Big Bend every which way from windshield touring to paddling on the Rio Grande through every canyon to a six day, eighty-mile hard hike from Rio Grande Village to Lajitas, with the backpack saddle sores to prove it. I like to think I’ve explored a fair amount of this exceptional place since I first saw it sixty years ago, enough to have formed some opinions and to have noticed the changes in the timeless landscape.

As much as I thought I knew the Big Bend, it took a flight with Marcos Paredes in his Cessna 205 to underscore how little I really do know. Paredes is Rio Aviation, a one-plane operation in the greater Study Butte-Terlingua-Lajitas-o-plex. He’s also a river runner, retired park ranger, and veteran horseback guide who knows the Big Bend intimately.

He was a font of information during our hour flight covering Terllingua, nearby mines, the Rio Grande, the Mesa Anguila, and Santa Elena Canyon. From six thousand feet up, the Solitario, a circular collapsed caldera in Big Bend Ranch State Park, finally made sense in a way it didn’t from the ground. Santa Elena Canyon from up high more closely resembled a crack in a seabed than a canyon with soaring walls. Between the views and Paredes’ observations, the flight was as thrilling as the first time I saw the Window in the Chisos Basin as a child.